Deep in the Dead: The Chronicles of Individual Assassins

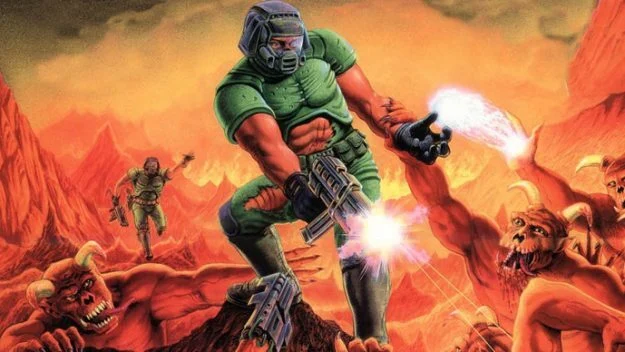

When it comes to shooting people in video games, a lot has changed since the release of Doom in 1993. Let’s grind through nearly three decades of gore and guts.

The first-person shooter genre may be the one that best describes a video game. Consider it. What kind of game does a TV show’s intended gamer character often play? 99% of the time, they’ll be using the Internet to stalk enemies and gaze down iron sights. The idea has a certain purity about it. Not an avatar to squirm around like a puppet on television. Your eyes serve as your monitor. Your rifle, your mouse. There is an instantaneous and direct connection.

In the more than 50 years since its release, first-person shooters (FPS) have seen ups and downs in popularity. However, new concepts from game developers bring the genre back to life with every generation. This article traces the origins of the genre and its current progression, covering every notable first-person shooter game released on major platforms. We will limit our discussion to first-person shooter games where the majority of player movement is done on foot, such as Descent. In the comments section, please let us know if we missed any important games. Watch the gameplay videos that are linked throughout!

View It From Your Perspective

The field of computer graphics was undeveloped in the 1970s. Programmers began figuring out ways to make fascinating things happen to those pixels after systems transitioned from punchcards to pixels on a screen.

According to historians, the first serious attempt at a first-person shooter was Maze War, developed in 1973 for the NASA Ames Research Center’s Imlac PDS-1 computers. The game allowed several users to navigate a 3-D maze one “tile” at a time while shooting other players (represented by eyeballs) when they came into view. Steve Colley was the first developer to receive credit for the game. Though awkward, no such thing has ever been attempted before.

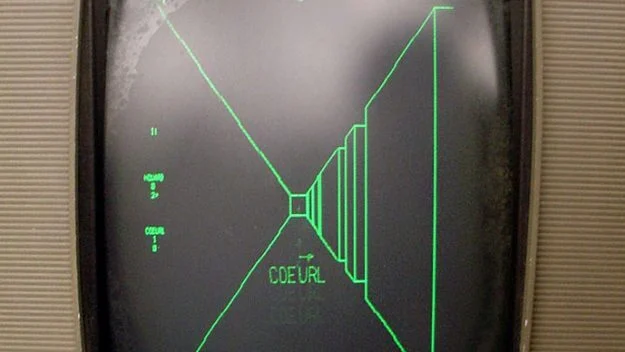

In 1974, networked PLATO computers launched Spasim, a portmanteau for “Space Simulator.” This gave you control of a spaceship instead of a person and rendered a three-dimensional world in wireframe. In case you were under the impression that these early games were enjoyable, you should know that the screens would only refresh once every second due to the extremely low framerate of the technology at the time. A few years later, Panther, a tank simulation, would emerge from later versions of the game and be released in arcades.

Put in Coin

The arcades are where any history of video gaming must begin. This was the main destination for gamers in the 1980s, when cutting-edge hardware drove fresh and inventive innovations in game creation. Though first-person shooter games are usually associated with home computers, arcades did host some early examples of the genre as well as some unique variations on the theme.

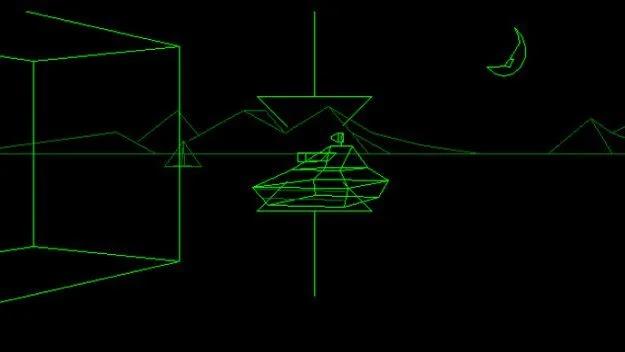

Atari’s 1980 Battlezone is arguably the most significant arcade antecedent of the first-person shooter genre. Players took control of a lethal assault tank in this vector-rendered game, which let them to rotate and move in any direction over a featureless environment peppered with geometric solids and hostile opponents. Although it’s simple, everything that matters is there.

One arcade game, Wizard of Wor by Midway from 1981, is the most intensely similar to early first-person shooters. It was basically Doom seen from above, with players navigating a treacherous maze plagued with deadly animals and even having the ability to shoot each other in two-player mode.

Taito’s Gun Buster, which debuted in the same year as Doom, was the first free-roaming first-person shooter arcade game. It was operated by an odd combination of a light pistol for aim and firing and a joystick for movement; cabinets could be networked together to play multi-player deathmatches.

The Maze Runner

Hybrid Arts’ 1987 Atari ST game MIDI Maze was the first genuine first-person shooter on a home computer. It placed players in control of a ball that resembled Pac-Man in a maze with a right angle, allowing them to move in any direction and launch lethal bubbles at other Pacs.

MIDI Maze’s networking feature was what drew me in so much. The game may interface with up to 16 players in the same maze by using the MIDI in and out ports normally assigned to sound recording and processing (however more than 4 players usually resulted in extremely high latency). Deathmatch competitions were entertaining, particularly since users could design their own labyrinths using a basic text editor.

A Faceball 2000 version of MIDI Maze was launched in 1991 for the original Game Boy. It was possible to network up to 16 portable consoles together for intense deathmatches by using an odd hardware hack. But this game didn’t sell well and was more of a curiosity than anything else.

Like a Wolf, Hungry

We haven’t even reached Doom yet, yet we’re nearly at the thousand word mark. Remain composed, my friend. This is the moment to introduce you to the men who would change first-person shooter gaming forever.

John Carmack, Adrian Carmack, John Romero, and Tom Hall—all workers at publisher Softdisk—founded iD Software. Beginning with the side-scrolling Commander Keen game from 1990, the team was able to extract amazing performance from the PCs of the day because to John Carmack’s technical wizardry. Carmack’s breakthrough in rendering 3D settings at the same speed as 2D environments spurred the fledgling company to innovate even more.

Raycasting was first introduced by Carmack in the game Catacomb 3D, which broke free from the confines of flight simulators and other specialized software by having the computer only draw what the player could see instead of the entire environment.

In 1992, iD’s Wolfenstein 3D, an unofficial continuation of the renowned adventure game Castle Wolfenstein, was released as shareware. This new game places players directly in the skull of Allied spy William “B.J.” Blazkowicz, who is massacring Krauts within a Nazi prison. The previous game placed players in a 2D elevated view. Unlike the slower-paced fare of the day, John Romero and Tom Hall pushed the experience to be rapid and visceral, keeping players continually on the edge of their seats.

After selling 200,000 copies in a single year, the game’s publisher Apogee ordered follow-ups and even released an anthology of 800 (!) user-made levels. It was an enormous smash and the pioneer of a brand-new genre.

And then Doom appeared, eighteen months later.

Large-scale f***ing game

Wolfenstein’s popularity allowed iD to pursue their passions, and they were hungry for more. Their new game would be powered by Carmack’s highly ambitious engine and would be bigger, quicker, bloodier, and scarier. They had all they needed, but for a few detours to create Hovertank 3-D (faster rendering) and Catacomb 3-D (texture mapping to surfaces). The group could now create floors with variable elevations, apply bitmap textures onto 3D objects, and light different places with different intensities of light. After Carmack reworked the idea to center on technology vs demons after his attempts to obtain the Aliens license failed, Doom was formed.

The main character, “The Doomguy,” is a space marine thrust into what seems like never-ending conflict with a swarm of demonic foes, each of whom has special moves and ways of acting. The fact that Doom’s creatures interacted with the player and lived in a recreated ecology was one of the games’ most captivating features. Add a brutal, visceral music, and you got a visceral experience that helped establish a genre.

The game was an immediate hit and greatly influenced many others, many of whom used Doom’s engine in their own creations.

Doom’s Children

Unfortunately, Apogee’s Blake Stone: Aliens of Gold came out a week ahead of Doom, so by the time it reached stores, it was out of date. However, Blake Stone: Planet Strike, a sequel, was released. Both were skillful, although uninteresting, interpretations of an already-old formula.

With the release of Doom came the first major wave of shooters, thanks in part to iD’s helpful licensing of their technology to other firms. They didn’t care that they were losing at their own game because they were working on a sequel that wouldn’t interfere with their success. In Doom 2, the game’s multiplayer features were optimized for dial-up modems, while new monster kinds and larger areas were included. The Final Doom of 1996 was, well, not the final Doom. Instead, it showcased levels created by the hobbyist group TeamTNT, which iD would soon buy.

Though it added inventory management and allowed the player to gaze up and down, Raven Software’s Heretic didn’t much differ from its predecessor. They planned to issue a spin-off series in Hexen in addition to the sequel, Shadow Of The Serpent Riders. Players could select from three different character classes in Hexen, and they could visit hub sections and side paths that required more retracing and exploration.

Apogee proceeded to invest its Wolfenstein funds in more first-person shooter titles, such as Rise of the Triad (1994), which offered players the option to select from five distinct characters with varying abilities. It also contributed to the popularization of the idea of “gibs,” which are grisly bits of meat that are shot loose from dying foes. The game also had some basic physics and destructible environment elements.

The 1996 game Rogue’s Strife introduced a few light RPG aspects to the concept by letting players level up and interact with NPCs in the game world. Although not highly accepted at the time, it had an impact on some important games that were released soon after.

Fewer developers worked on the Macintosh platform, although in its early days at least one iconic first-person shooter made the switch. Bungie mixed Wolfenstein-style shooting and labyrinth running with an inventory system and a text journal of your actions in their 1993 game, Pathways Into Darkness.

The second game from the studio, Marathon, significantly improved multiplayer gaming by including voice chat across local area networks and the option to use two weapons. The Seattle newspaper I worked for right out of high school used to host enormous all-night Marathon sessions, which is how I first became aware of playing first-person shooters.

System Shock, released in 1994, was a significant advancement that pushed for greater immersion and more engaging story. The game pitted players against a malicious artificial intelligence on a deserted space station. It would serve as the basis for several sequels, both directly and indirectly, since the Bioshock franchise drew heavily from it.

After launching as side-scrolling platformers, the Duke Nukem series entered the third dimension in 1996 with Duke Nukem 3D. This was the first first-person shooter game that truly made its protagonist a celebrity, with Jon St. John’s voice giving Duke quips to make while he destroyed pig-like aliens.

In addition, Creators 3D Realms introduced the Shadow Warrior series, which refined the model by adding transparent water, enhanced level geometry, and sexual themes. Reboots and sequels came and went over the years.

The B-rate knockoffs and Doom-alikes that soon overflowed the market, such as Gore Galore, H.U.R.L., and William Shatner’s TekWar, could fill a whole article. They didn’t bring anything significant to the genre; that would have to be done by iD again.

Moving Polygons

The main drawback of the Doom engine was that character and object art had to be created using sprites in games. Although they never fully fit in with the rudimentary polygonal landscapes, the machines of the day were unable to render the surroundings and people in three dimensions with ease. Things may get quite fascinating once that was rectified.

With the 1996 release of Quake, iD was the developer to lead the way once more. The ambitious project changed from being a 3D fighter inspired by Sega’s Virtua Fighter arcade game to something the team felt more at ease with: a shooter set in a gloomy medieval setting including Trent Reznor’s music. Players had more movement choices in fully 3D landscapes, and Quake popularized the idea of “rocket jumping,” which involved launching your avatar across the level and high into the air utilizing the blowback from your explosive weaponry.

Still, there were heirs to the kingdom. Unreal, developed by Epic using its own engine and including some really interesting features, was released in 1998. Modders found it to be a veritable feast thanks to an editor that provided real-time geometry placement and a scripting engine. Over the following twenty years, the Unreal engine would develop into one of the most dependable pieces of middleware in the business, and not just for shooters.

First-person shooter games developed with the original Unreal Engine include the Wheel of Time series adaption and Star Trek: Next Generation: Klingon Honor Guard.

Man to Man

First-person games have always had competitive multiplayer, but in the late 1990s, with the development of the national Internet infrastructure, it became quite simple to discover other players, especially on college campuses equipped with lightning-fast T1 lines.

Unreal Tournament, one of the first first-person first-person shooter games, was released by Epic in 1999. The online and LAN gameplay was the real meat, with the bare-bones singleplayer serving as a means of preparing people against bots. Due of its enormous success, the game encouraged many to embark on related projects.

Quake III Arena, which was released later that year, was iD’s response. With a focus on quick movement and a high skill ceiling, it was a masterfully designed game that avoided cramped hallways in favor of wide arenas designed for online play.

Starsiege: Tribes by Dynamix, which marketed itself as the “world’s fastest shooter,” was in a similar line. In the game, players controlled armed mechs in expansive outdoor settings. They also found a movement bug known as “skiing,” which allowed them to maintain momentum by timing jumps while going down a hill. You could go incredibly quickly across the map by doing that.

Recounting Tales

The majority of early first-person shooters had relatively little storyline. While players occasionally solved easy riddles and blasted anything that moved, they weren’t overly concerned with the plot or the characters. The 1998 release of Half-Life compelled the industry to significantly step up its game. In Valve’s groundbreaking game, physicist Gordon Freeman—a silent protagonist typically found in Japanese role-playing games—sailed across the Black Mesa facility in a seamless, cutscene-free environment. As a result, environmental narrative became one of the genre’s essential components.

However, there were also drawbacks to Valve’s strategy: the player-driven, nonlinear gameplay of previous games was replaced with a more linear experience that not many developers could match.

One of the most highly praised efforts was the Bioshock trilogy, which placed players in intriguing, meticulously designed environments where they had to balance moral and ethical dilemmas while wielding superhuman abilities and destroying enemies.

The Actual World

First-person shooter simulations becoming increasingly realistic as technology advanced. Players weren’t content to just shoot and turn switches while circling a flat plane. In order to truly live in these fantastical realms, creators required physics. That would let in a ton of new worms, both beneficial and detrimental.

Jurassic Park: Trespasser was among the first video games to truly emphasize physics as a central component of the experience. You could crudely manipulate boards and boxes, which responded with simulated collisions based on the laws of motion we encounter on a daily basis, as the main character Anne. Their model’s inaccuracy resulted in invisible boxes around objects to indicate collisions, which made exact manipulation terrifyingly difficult.

The popular military thriller novelist Tom Clancy’s fictitious universe was licensed for use in Tom Clancy’s 1998 game, Rainbow Six, which served as a tactical shooter and warned players that even one bullet may be fatal. Rainbow Six does away with the run-and-gun style of gameplay found in Doom, requiring you to carefully plan your assault because one mistake may be deadly. A whopping ten sequels to the game were inspired by its enormous success.

A response to Quake’s childish exaggeration was also seen among players who preferred something a little more realistic. In 1999, a Half-Life mod called Counter-Strike was created, which featured teams of terrorists and counter-terrorists competing against one another in missions with predetermined objectives. The way the game handles death is one of its largest departures from custom: in CS, there is no respawning. Every move counts since deceased players are forced to watch till the next round begins. It gained enormous popularity and sparked the emergence of a rival scene.

The first Medal of Honor video game was released on consoles in 1999. The game, which had a scenario by Steven Spielberg, immersed players in the heat of World War II and included thrilling battles with some of the most sophisticated opponent AI available at the time. A multiplatform franchise that would last until 2012 was started by the game.

Battlefield 1942, a long-running brand that focuses on World War II and offers competitive and cooperative multiplayer, entered the market in 2002. More than a dozen games would be included in the Battlefield series; the most current being the futuristic Battlefield 2042.

Take Your Own Approach.

Some designers began to push the boundaries farther in opposition to shooters with a linear storyline. Thief: The Dark Project, released in 1998, gave players a wide range of abilities and turned them loose to accomplish areas anyway they saw fit, with an equal emphasis on stealth and fighting.

This idea persisted in Warren Spector’s seminal first-person shooter Deus Ex from 2000, which focused entirely on alternatives. There were several ways to solve every issue, ranging from complete destruction to cunning and hacking, which produced a game that redefined the genre and raised the standard for first-person adventure.

This way of thinking would continue to influence game developers that wanted to create more immersive and cerebral experiences, like in the case of CD Projekt RED’s ambitious but unfinished Cyberpunk 2077. These games combine classic action gameplay with other avenues for world interaction, such conversation, exploration, hacking, and more.

Party on the Console

First-person shooters have emerged as a primary motivator for PC gaming. Although Doom was ported to the Super Nintendo very well, the experience was quite poor in terms of networking. Despite this, some people still gave it a shot, and an extremely improbable developer succeeded in creating a console first-person shooter that became a classic.

Early implementations of the idea included Battle Frenzy (1994) for the Genesis, Metal Head (1994) for the Sega 32X, and Super 3D Noah’s Ark (1994) for the Super Nintendo, which was the first unlicensed SNES game ever produced and was essentially a Wolfenstein reskin with a Biblical theme.

The British business Rare was best known for its Nintendo games, such as the insanely challenging Battletoads. They had shown the big N their worth throughout three system generations, and they were chosen to handle a game based on the Nintendo 64 James Bond license. Goldeneye would be that game, proving that an FPS exclusive to a console could compete with the big boys.

Goldeneye used cunning technical tricks to get over the N64’s restrictions—no online play, for example. Even by the standards of the time, the game’s graphics weren’t all that amazing, but it was fluid and included a large variety of maps and weapons.

Perfect Dark, their sequel, was an improvement in many aspects, including enhanced graphics, more precise enemy artificial intelligence, and increased multiplayer options. Regretfully, framerates dropped since the N64 just couldn’t handle everything the game wanted to accomplish, which was a prevalent issue on the dated systems.

With Turok for the Nintendo 64, publisher Acclaim—notable for their investment in licensed titles—took a tentative step into the genre. Developer Iguana Software challenged Nintendo’s reputation for family-friendly games and pushed the machine to its boundaries, making it one of the most popular third-party titles on the system.

The strange Jumping Flash, Kileak: The DNA Initiative, a Japanese game featuring a mechanical rabbit capable of enormous vertical leaps, and a dreadfully boring South Park game for the PlayStation and Nintendo 64 were among the other first-person shooters available on early home systems.

Strange Things

Since everyone and their mother wanted to get into the first-person shooter business, the genre saw some rather unique approaches during its golden age. According to the box, Forbes Corporate Warrior is a manual for contemporary business. It’s actually among the worst first-person shooter games ever created, allowing players to destroy competing companies with “Ad Blasters” and “Marketing Missiles.”

To market its cereal Chex, General Mills engaged developers Digital Café in 1996 to create a free game. As a result, the Doom engine was integrated with the popular blaster Chex Quest, which allows you to destroy foes using cereal and milk. The game was remarkably revived in two different years, 1997 and 2008, and was given an HD remake for the Nintendo Switch in 2022.

Using the Pie in the Sky engine, Terror in Christmas Town is a spooky, retro holiday game in which you have to save Santa Claus from an evil polar bear that has kidnapped him.

Cyberdillo, a seemingly comical shooter that depicted the player as a roadkill armadillo upgraded with mechanical parts and embarking on a mission of vengeance, was released in 1996 for the doomed 3DO system. One of the jokes in the game was a “bone flute” weapon that, if used, rendered the player blind.

With a production budget of about a million dollars, N’Lightning Software created the unique computer game Catchumen in 2000. It is still one of the most costly Christian video games ever made. In the First Person Shooter, you take on the role of a Roman student who must explore a number of catacombs in order to save friends and strike Satan. In the game, human adversaries that you “kill” bow down in supplication.

The Game of Waiting

Early on, developers released games quickly and furiously. There was hardly a year that passed between Doom and Wolfenstein 3D. But FPS games became more and more labor-intensive to create as designers became more ambitious and technology became more sophisticated. The industry went through a phase of protracted delays and repeatedly rescheduled release dates.

John Romero attempted to join the narrative bandwagon with the much-awaited, much-hyped Daikatana in 2000. The project already appeared outdated and had to convert to the Quake II engine halfway through development, a process that took more than a year in and of itself. Originally, it was supposed to be finished in seven months from start to finish and released for Christmas 1997. The game wasn’t worth the wait, especially when you consider that the E3 demo only operated at 12 frames per second.

When 3D Realms began development of Prey in 1995, they wanted it to be at the forefront of technology, acting as the foundation for their own in-house engine. They were unable to complete the project, therefore in 2000 the game was shelved. However, it was later revived and released to strong sales. The 2017 relaunch of the property is fantastic but largely unrelated.

Duke Nukem Forever, which was first announced in April 1997 and eventually published in 2011 after a 14-year development period, was the epitome of first-person vaporware for a long time. The game had several engine changes over that period, and upon its release, it faced harsh criticism from critics, which served as the last straw for the franchise.

The only game that first-person shooter fans have been waiting longer for is Half-Life 3, a project from Valve that might not materialize in our lifetimes. Since Episode 2 in 2007, there hasn’t been a new game in the series, and Valve is infamous for keeping quiet about internal development projects.

Engine Wars

Other software developers saw a way to become well-known and wealthy by developing their own 3D engines that they could reuse and license after iD gained notoriety with Doom and opened up its source code to the public. Here is a summary of a few of the most noteworthy.

Programmer Kevin Stokes was largely responsible for creating the “Pie in the Sky” engine, which he used for first-person shooters such as Terminal Terror and Lethal Tender. Subsequently, the program was retailed as the 3D Game Creation System, and several small teams purchased and utilized it to build games such as Red Babe and the bizarre Pencil Whipped.

Unexpectedly, a small Croatian development team known only as “Croteam” developed their own engine to power Serious Sam, a fast-paced, retro-styled run-and-gun game with an enormous number of adversaries and a fluid, fluid gameplay.

After releasing their CryEngine in 2004’s Far Cry, German developers CryTeam gained notoriety for being exclusively concerned with the best hardware available. With Crysis and its sequels, which produced astounding, almost cinematic realism, they continued to refine the engine.

Pride of Spartans

Following Marathon’s popularity, Bungie took a break to experiment with other genres. But they would alter the game irreversibly when they returned to the first-person shooter at Microsoft’s request. When Halo: Combat Evolved was originally announced in 1999, it was released as an Xbox launch title. Master Chief used precise controls and entertaining vehicles to face a variety of aliens in this 26th-century game.

Several advancements from Halo made playing first-person shooter games on consoles more feasible. The most noteworthy was arguably the regenerating shield, which allowed players to suffer damage and recover by just pausing the game for a short while. That compensated for the reduced accuracy that came with using a controller. Xbox Live play was added to LAN multiplayer and local split-screen gaming for the sequels.

Before leaving, Bungie worked on two additional Halo sequels, a prequel, and an expansion for Halo 3. Microsoft then handed over control of the series to 343 Industries.

Listen for the Call

The early 2000s World War II game boom gave rise to the Call of Duty franchise. The first several games in the series, which were published by Activision, were capable, lifelike infantry simulators that highlighted AI squadmates. However, the release of Call of Duty 4: Modern Warfare in 2007 signaled a change in the series’ direction and helped it become one of the most well-liked titles available.

Players engaged in combat with terrorists and insurgents throughout the Middle East and Eastern Europe in this asymmetric warfare simulation. It was the best-selling game of the year thanks to a compelling plot with a few surprising emotional turns and a creative, responsive multiplayer mode.

The series keeps chugging along, with newer entries setting the scene in the future and giving soldiers superhuman mobility capabilities. Ironically, a series that began with realism has evolved into what it is now, but it doesn’t stop the games from being successful.

Console Retaliation

Halo paved the stage for a console renaissance in first-person shooters, as creators at last found practical alternatives to the conventional keyboard and mouse.

The PlayStation 2 debuted in 2000 with a first for a console: first-person shooter. TimeSplitters was a critical hit and the sequel was even better. The game was developed by Free Radical, a firm comprised of former workers of Rare who worked on their last-generation shooter. The addition of a level editor greatly increased the replayability of the game.

When Nintendo gave American developer Retro Studios control of the typically side-scrolling Metroid franchise in 2002, it was one of the biggest risks in the genre. Metroid Prime, the ensuing GameCube title, breathed new life into the genre by prioritizing movement and exploration above aimless shooting. There were two more, and a fourth, long-awaited installment is said to be coming to the Switch as soon as it’s ready.

Combine

Team Fortress is a 1996 mod for multiplayer Quake that has withstood the test of time. Nine distinct classes were available for players to choose from in the game; each class had unique weapons, health pools, and mobility speeds. The emphasis on teamwork rather than “every man for himself” deathmatch gameplay became instantly popular, and Valve acquired the team behind the mod to use them on 2007’s Team Fortress 2 and a Half-Life engine conversion. The cartoonish art design and refined gameplay of the sequel combined to make it one of the most continuously played first-person shooter games of the past ten years.

Additionally, Valve created Left 4 Dead, a game that popularized asymmetric survival-based multiplayer in which players took control of either strong zombies or armed humans battling the undead. The artificial intelligence “director” in the game was designed to keep things interesting by adjusting the pacing when playing together. A sequel was released, and the development team Turtle Rock was taken over by Tencent, a massive Chinese company, after being fired from Valve. Back 4 Blood, their most recent game, goes back to the dish that first brought them fame.

In terms of team-based shooters, Overwatch represents the pinnacle of the genre in recent years. It features an incredibly colorful cast of characters with unique skills that combine to provide a plethora of intriguing strategic possibilities. With this game, developer Blizzard—who hadn’t done much in the first-person shooter genre—has proven that they can produce a well-executed, original idea. What the follow-up, which is due out in October 2022, will include is still up in the air.

Apex Legends and Valorant are two more “hero shooters” with sizable fan bases; the latter employs a more violent Counter-Strike style of gunplay.

Now let’s try something new.

As the first-person shooter genre solidified as one of the most well-known in gaming, fringe experiments began to appear. Teams started to challenge the genre’s conventions, questioning if deathmatches, stern protagonists, or even weaponry were necessary.

The Portal from 2007 is recognized for having opened the gates. Using a “weapon” that creates gaps in space between locations, the main character Chell has to defy the laws of physics in order to escape a research center full of lethal experiments. Both games were replete with clever, sardonic humor, and the sequel added even more features.

Mirror’s Edge, an apparent first-person shooter that put movement above gunplay, was released by EA that same year. Although the main character Faith have the ability to shoot a gun, the main focus of the game was traversing an enormous environment made up of pipes, shafts, and roofs with remarkable freedom, akin to parkour. The 2022 smash Neon White puts the emphasis on traversal and blends it with a smart card-based weapon system for speedruns. It was a cult hit that spawned a 2016 sequel.

One amazing recent example is the abstract shooter Superhot, which twists the frenetic speed of a traditional first-person shooter by having time advance only when you do. If you remain motionless, bullets will linger in midair, but if you make a mistake, they will strike your face directly. Nothing on Earth compares to the frantic ballet of split judgments and polygonal destruction that each level entails. There’s even a VR version available.

Other intriguing first-person shooter experiments include the abstract Lovely Planet, the hyper-realistic gun simulator Receiver, which requires players to meticulously load and prepare their weapons, and the PS3 title The Unfinished Swan, which begins with an entirely white area that the player must fill with ink to explore.

Glancing Back

The “boomer shooter” microgenre, which is one of the most well-liked FPS subgenres at the moment, consists of games that forgo all of the sophisticated features of contemporary games like Call of Duty in favor of concentrating on the gameplay’s essential components: movement and blasting. Although these are frequently handmade projects by small development teams, the influence of boomer shooters is beginning to permeate the AAA market.

Dusk by David Szymanski was one of the genre’s pioneers. When it was first published in 2018, its gritty low-poly look left many confused. When you turn it on, it even includes a phony DOS startup screen. However, Boomer shooters thrive or perish based on how much fun and instantaneous they are to play; Dusk and the like don’t coast on nostalgia. These games are popular because they offer fast-paced, quick action without any of the extras that modern first-person shooter games adore, like narrative clumsiness or loot grinding.

Other noteworthy additions to the trend are the gleefully silly Turbo Overkill, the only first-person shooter that permits you to wield a chainsaw on your leg, and Prodeus, which takes the aesthetics of Doom and applies a chunky pixel filter to produce something that feels somehow older than its inspiration.

Furthermore, Nightdive, a development firm, has established a strong business by remastering old-school shooters such as Blood, Quake, and Turok. They were made in response to artist Stephen Kick’s discovery that he could not buy his favorite System Shock 2 for a contemporary platform. Now, a grateful new audience has been introduced to the glory of these groundbreaking classic games.

In the Future

First-person shooter games are still quite popular, with both established series and recent releases causing waves in the industry. The Wolfenstein series is back in style, Call of Duty releases a game roughly every year, a new Doom was launched in 2020, and the “games as service” movement means that titles like Overwatch and Destiny 2 receive regular updates with new material.

It seems sense that virtual reality is establishing itself as a key platform for the genre. While there hasn’t yet been a really system-selling game among them, certain excellent titles like Farpoint for the PSVR and the eagerly anticipated Half-Life: Alyx from Valve are showing that the potential is there. The largest problem with VR games is still control; it’s difficult to truly feel like you’re running and strafing while you’re stationary.